Hanno scritto sull'artista

Stefania Carrozzini; Elisabeth Frolet; Donato Di Poce; Bruna Condoleo; Vittorio Sgarbi; Daniela Ciotola; Simonetta Baroni; Simon Altmman; Francesco Gallo; Vera Pitzalis; Emanuele Bissattini; Giulia Sillato; Anna Mola; Francesca Facchetti; Vincenzo Morra.

Da: “I giudizi di Sgarbi”

Vittorio Sgarbi, Mondadori 2005, Milano

Francesco Pezzuco works on an abstract painting that often brings to the surface recognizable shapes, minute like footprints. The artist has evidently opted for a pictorial key linked to a sort of discipline of thought. The signal of this philosophical vocation also filters through the titles of his compositions, such as the point of affection of the artist for a point of the earth...

Other paintings are instead linked to the relationship between man and nature, or to what exists between heaven and earth, themes that he deals with in symbolic geometries of great intelligence. This also applies to the series of works thematically unified under the denomination of Stanze and which develop the parallel themes of dream and sound. It takes a certain conceptual boldness to visualize similar arguments in a not elusive way, and Francesco Pezzuco is certainly not lacking in this dowry. The sense of the dreamlike, as well as that of harmony rely on a geometric vision that evokes a cosmic balance regulated by a non-transcendent reason, or rather by the laws of a nature enunciated as a vital matrix and ethical finality.

Francesco Pezzuco opera su una pittura astratta che spesso riporta in superficie delle forme riconoscibili, minute come delle impronte. L’artista ha optato evidentemente per una chiave pittorica legata a una sorta di disciplina di pensiero. Il segnale di questa vocazione filosofica filtra anche attraverso i titoli delle sue composizioni, come il punto di affetto dell’artista per un punto della terra...

Altri dipinti sono invece legati al rapporto fra l’uomo e la natura, o a quanto intercorre fra il cielo e la terra, temi che egli affronta in geometrie simboliche di grande intelligenza. Questo vale anche per la serie di opere unificate tematicamente sotto la denominazione di Stanze e che sviluppano i temi paralleli del sogno e del suono. Ci vuole una certa arditezza concettuale per visualizzare in modo non elusivo simili argomentazioni, e di questa dote Francesco Pezzuco certamente non manca. Il senso dell’onirico, così come quello dell’armonia si affidano a una visione geometrica che evoca un equilibrio cosmico regolato da una ragione non trascendente, o piuttosto dalle leggi di una natura enunciata come matrice vitale e finalità etica.

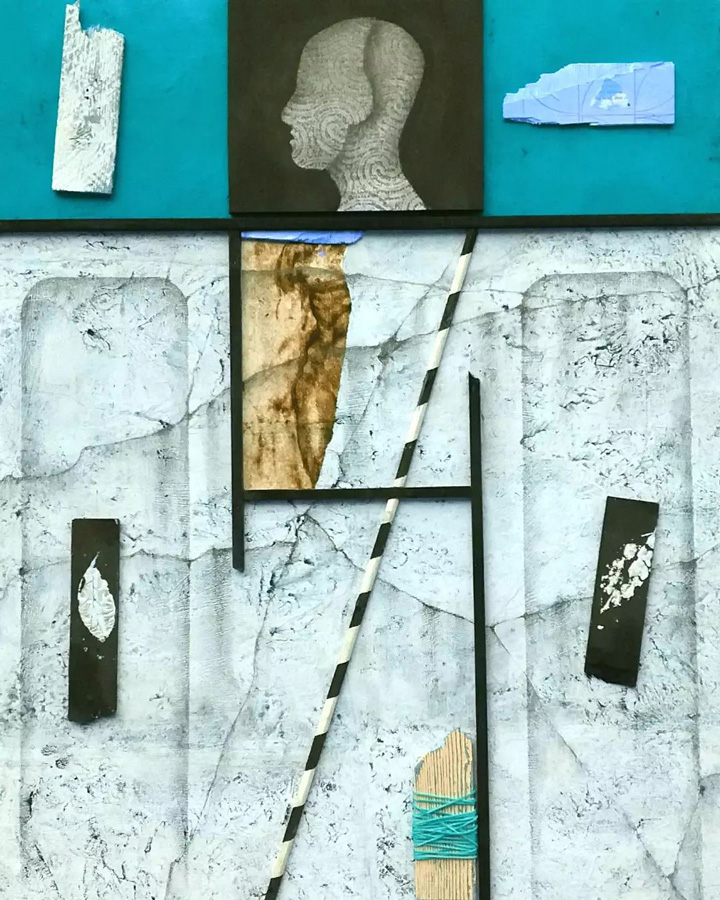

frammenti diversi

"l'anticamera del pensiero"

(installazione)

"l'anticamera del pensiero"

(installazione)

ScriptaVolant

A review by Giulia Sillato

Trilogy is a term that suggests broad historical periods, describing an evolving of phenomena. Thus have I identified the various creative phases of Maestro Pezzuco, because what is acted out on the Maestro’s “small screen” (where with “small screen” I mean the surface of his pictorial work) is conceptually broad. He opens up a discourse linking the History of Man, of Art and of Modern Communication...

Wishing to give an account of the Maestro’s output, we see that there are three definable phases in his artistic expression and style, which can now be established once and for all. In the first phase of his work, a very intimate relationship with MATTER was developed, so that this became the protagonist of the themes presented. The main theme, then as now, was centred on the dialectic MAN – NATURE and the material components were called upon to render explicit and tangible his Discours sur la Nature perdue par l’homme. With ‘tangible,’ I mean tactile, where an earthly presence in the shape of leaves, stones, shells, ropes… can actually be touched within the painted ensemble on its wooden support.

In the second phase of his work, the Maestro meditated further on a subliminal level so that the resulting artistic expression acquired a lightness, an intangibility, an airiness. A system of signs was spread out onto the painted plane, a plane for communication. These are free floating, airy signs, as though suspended in the infinite, in a world without boundaries, while colour dissolves into soft poetic tones and Matter – Mater is reabsorbed by a suspended atmosphere.

However, the concepts expressed were not within the grasp of all, being highly philosophical, rich in implicaton and, I would venture to say, psychoanalytic. This second phase, elevated and kaleidoscopic, left a definite mark in the public’s mind. Now a revision of this stage has evolved naturally to complete the trilogy of his creative art.

Here the Maestro softens the preceding dictats in an almost magical pictorial equilibrium. The dimensions have been slightly reduced and the surface of composition has been enriched with signs, with meanings that go beyond the perception of the senses. The viewer is urged to draw inspiration…not from the tactile, the immediate, but from the cerebral, in other words, to meditate.

Work from this last phase is exhibited in an unusual setting – not in an art gallery, not in a civic hall, nor along a street the bohemian way….but in the luxurious rooms of a hotel: the Elaia Garden Hotel. This is tantamount to being a one-man exhibition.

The paintings are almost all hung within the guest rooms themselves, defining the visual coordinates of their ‘box-like’ space. This space, within an essential, modern construction acquires a double dimension thanks to these works of art, and becomes the link between human Thought and Nature surrounding it (earth, sea, air…) a central theme to Pezzuco’s canto.

It is an arduous task to create such a communion with the natural environment, restoring its lost integrity and merited respect. Here at the Elaia Garden, there seems to have been a precise design for the architectural to be completed by the pictorial, just as once any building project called for all manner of Artists to contribute their work.

The works present at the Elaia are part, as we have said, of the third phase in the sequence, to which many other recent compositions belong. The term ‘trilogy’ is preferred to ‘period,’ though the latter is more usual in the description of progressive phases of artistic evolution. In this case, however, the evolution seems to have moved in broad conceptual phases, each one being a résumé of a sequence of layers of consciousness sedimented in historic memory.

Therefore, Pezzuco’s ‘zones’ summarise a collection of human experiences, which re-emerge in the Present as a symbolic elaboration to be fixed in the Future. These signs stay in the mind as a close-knit weaving of strokes, to be codified in the same way as today’s communication systems.

The work surfaces are now protected by sheets of plexiglass, while the medium is acrylic. There is no presence of other matter as was characteristic of the first phase. The paint progresses across vast chromatic backgrounds where the Maestro’s multi-faceted concepts are laid out on the various levels.

A hypothetical union between MAN and NATURE finds a different stylistic confirmation in this third phase, as it has been submitted to a different qualitative interpretation. The relationship between the two basic concepts of the artist’s ‘canto’ is loosened and the fibres which keep them united are unwound considerably to favour access to any element which threatens the equilibrium. It is a pitiless act of accusation - a polite, elegant, refined accusation, but still an accusation.

Human shapes are traced with the same extremism that characterised thirteenth century painting. They appear as though frozen within a wooden plate (superimposed onto the painted plane). Thus their totemic value is exalted, both on the existential plane as well as on the communicative level. They are drawn into the whole by the surrounding small signs and geometric figures which weave a background of unpierceable rings - not a concrete discourse.

The title of one of his recent works is “Il Giocoliere dell’Aria” [The Air Juggler] and this describes exactly the dynamics of these air signs which float away undisturbed…leaving no trace.

This is the drama played out by today’s communication, where in place of the VERBA VOLANT, we have SCRIPTA VOLANT…it is the drama of today’s humanity dispersed in spirit and unable to confirm its true values, true feelings, true emotions…

But time goes by inexorably… Bands of colour, juxtaposed in a spirited way, move dynamically across the painted surface, both horizontally and vertically, emulating the action of time…layering, sedimenting. The traces of one civilisaton are almost obliterated in favour of its successor, a gesture of renewal and trust.

The drama of “non correspondence” discovers a just aesthetic equilibrium in this formal elaboration of elements and in this material impasto. This is that rare, elevated, moment when Painted Art and the capacity to communicate through this medium, renders such a creation incredibly absorbing. In a daring intellectual gesture, the whole of humanity is brought back to its existential responsibility.

Perhaps it is time to define a new conceptual nucleus, a new mental state, a new aesthetic thought.

In the second phase of his work, the Maestro meditated further on a subliminal level so that the resulting artistic expression acquired a lightness, an intangibility, an airiness. A system of signs was spread out onto the painted plane, a plane for communication. These are free floating, airy signs, as though suspended in the infinite, in a world without boundaries, while colour dissolves into soft poetic tones and Matter – Mater is reabsorbed by a suspended atmosphere.

However, the concepts expressed were not within the grasp of all, being highly philosophical, rich in implicaton and, I would venture to say, psychoanalytic. This second phase, elevated and kaleidoscopic, left a definite mark in the public’s mind. Now a revision of this stage has evolved naturally to complete the trilogy of his creative art.

Here the Maestro softens the preceding dictats in an almost magical pictorial equilibrium. The dimensions have been slightly reduced and the surface of composition has been enriched with signs, with meanings that go beyond the perception of the senses. The viewer is urged to draw inspiration…not from the tactile, the immediate, but from the cerebral, in other words, to meditate.

Work from this last phase is exhibited in an unusual setting – not in an art gallery, not in a civic hall, nor along a street the bohemian way….but in the luxurious rooms of a hotel: the Elaia Garden Hotel. This is tantamount to being a one-man exhibition.

The paintings are almost all hung within the guest rooms themselves, defining the visual coordinates of their ‘box-like’ space. This space, within an essential, modern construction acquires a double dimension thanks to these works of art, and becomes the link between human Thought and Nature surrounding it (earth, sea, air…) a central theme to Pezzuco’s canto.

It is an arduous task to create such a communion with the natural environment, restoring its lost integrity and merited respect. Here at the Elaia Garden, there seems to have been a precise design for the architectural to be completed by the pictorial, just as once any building project called for all manner of Artists to contribute their work.

The works present at the Elaia are part, as we have said, of the third phase in the sequence, to which many other recent compositions belong. The term ‘trilogy’ is preferred to ‘period,’ though the latter is more usual in the description of progressive phases of artistic evolution. In this case, however, the evolution seems to have moved in broad conceptual phases, each one being a résumé of a sequence of layers of consciousness sedimented in historic memory.

Therefore, Pezzuco’s ‘zones’ summarise a collection of human experiences, which re-emerge in the Present as a symbolic elaboration to be fixed in the Future. These signs stay in the mind as a close-knit weaving of strokes, to be codified in the same way as today’s communication systems.

The work surfaces are now protected by sheets of plexiglass, while the medium is acrylic. There is no presence of other matter as was characteristic of the first phase. The paint progresses across vast chromatic backgrounds where the Maestro’s multi-faceted concepts are laid out on the various levels.

A hypothetical union between MAN and NATURE finds a different stylistic confirmation in this third phase, as it has been submitted to a different qualitative interpretation. The relationship between the two basic concepts of the artist’s ‘canto’ is loosened and the fibres which keep them united are unwound considerably to favour access to any element which threatens the equilibrium. It is a pitiless act of accusation - a polite, elegant, refined accusation, but still an accusation.

Human shapes are traced with the same extremism that characterised thirteenth century painting. They appear as though frozen within a wooden plate (superimposed onto the painted plane). Thus their totemic value is exalted, both on the existential plane as well as on the communicative level. They are drawn into the whole by the surrounding small signs and geometric figures which weave a background of unpierceable rings - not a concrete discourse.

The title of one of his recent works is “Il Giocoliere dell’Aria” [The Air Juggler] and this describes exactly the dynamics of these air signs which float away undisturbed…leaving no trace.

This is the drama played out by today’s communication, where in place of the VERBA VOLANT, we have SCRIPTA VOLANT…it is the drama of today’s humanity dispersed in spirit and unable to confirm its true values, true feelings, true emotions…

But time goes by inexorably… Bands of colour, juxtaposed in a spirited way, move dynamically across the painted surface, both horizontally and vertically, emulating the action of time…layering, sedimenting. The traces of one civilisaton are almost obliterated in favour of its successor, a gesture of renewal and trust.

The drama of “non correspondence” discovers a just aesthetic equilibrium in this formal elaboration of elements and in this material impasto. This is that rare, elevated, moment when Painted Art and the capacity to communicate through this medium, renders such a creation incredibly absorbing. In a daring intellectual gesture, the whole of humanity is brought back to its existential responsibility.

Perhaps it is time to define a new conceptual nucleus, a new mental state, a new aesthetic thought.

Ho preso l’abitudine di identificare i vari periodi creativi del Maestro Pezzuco. “Trilogia”: questo è un termine che suggerisce larghe periodizzazioni storiche, legate a fenomenologie evolutive di grande interesse artistico.

In effetti è quel che si recita sul “piccolo schermo” del Artista e per “piccolo schermo” intendo la superficie della sua Opera pittorica, piccola dimensionalmente, ma grande concettualmente…

In effetti è quel che si recita sul “piccolo schermo” del Artista e per “piccolo schermo” intendo la superficie della sua Opera pittorica, piccola dimensionalmente, ma grande concettualmente…

...talmente grande da riassumere insieme in una unica prospettiva concettuale non solo la Storia dell’Uomo, ma anche della Storia dell’Arte e, ultima, la moderna Vicenda delle Comunicazioni.

Volendo fare il punto della situazione nell’ambito della produzione del Artista, ci troviamo di fronte a tre passaggi espressivi e stilistici ben precisi, che sollecitano di essere messi a fuoco e fissati una volta per tutte: nella prima fase del suo lavoro egli sviluppa un rapporto molto intimo con la MATERIA, tanto da assumerla a protagonista indiscussa dei temi trattati e poiché la tematica, allora come anche oggi, verte sul binomio puro UOMO —NATURA, le componenti materiali utilizzate erano chiamate a rendere esplicito e tangibile il suo Discours sur la Nature perdue par l’homme e per “tangibile” intendo sensibile al tatto, nel senso che si potevano toccare con mano alcune presenze terrene come foglie, sassi, conchiglie, spaghi… il tutto organizzato in ensemble con paste cromatiche su lastre lignee tradotte in contenitori.

Nella seconda fase del suo lavoro l’Artista spinge la sua meditazione a livelli subliminali, al punto che la derivante espressione artistica acquisice leggerezza, impalpabilità, ariosità mentre il sistema segnico si dirada sul piano della comunicazione, che è anche il piano della pittura, in segni liberi, aerei, come fluttuanti nell’infinitezza di un mondo senza confini, mentre il colore si discioglie in tonalità soffici e poetiche, mentre la Materia —Mater (per evocare un concetto boccioniano) si riassorbe in un clima sospeso e atmosferico.

Ma la concettualità, soprattutto se improntata a filosofie dense e ricche di risvolti, oserei dire, psicoanalitici, non è cosa di tutti e questo momento della creatività d Pezzuco, pur alto e caleidoscopico, ha lasciato un segno indelebile nella fruizione pubblica… La revisione che ne è naturalmente scaturita ha originato la trilogia della sua creazione.

Qui l’Artista ristempera i dettati precedenti in un’equilibrio compositivo e pittorico che ha del magico: le dimensioni si sono leggermente ridotte e la superficie della tavola si arricchisce di significazioni segniche che vanno al di là della percezione sensibile, sollecitano lo spettatore ad un diverso godimento… non quello del tattoriale e dell’immediato, ma quello del cerebrale e del meditato.

Una parte di quest’ultima produzione è esposta in spazi inusuali per una mostra d’Arte: non la solita galleria, non la solita sala civica, ma le lussuose stanze di un Albergo: Elaia Garden Hotel che raccoglie, come in una grande personale, numerose opere del Maestro, quasi tutte collocate sulle pareti delle camere a convogliare l’impatto ottico di chi entra nella stanza e definire così le coordinate visive dell’intera scatola spaziale che, inserita in una costruzione modernissima e stilisticamente essenziale, riesce a vivere, attraverso queste opere, una seconda dimensione, trasformandosi in una struttura ponte tra il Pensiero umano e la Natura circostante (terra, mare, aria…), tema centrale del canto pezzuchiano.

Non è da tutti riuscire a creare un aggancio simile all’ambiente naturale, restituendo ad esso l’integrità perduta e il rispetto che merita… molte organizzazioni d’accoglienza turistica, quando decidono di arricchire le proprie collezioni d’Arte, lo fanno in maniera impropria e mistilinea, mentre qui, all’Elaia Garden, sembra si sia seguito un disegno preciso per attuare con i mezzi dell’Architettura e della Pittura un’opera completa come quelle che un tempo gli Artisti erano chiamati a compiere.

Le Opere presenti all’Hotel Elaia fanno parte, come si è detto, della terza sequenza ciclica del Maestro, alla quale peraltro appartengono anche molte altre composizioni realizzate recentemente ed è in tal senso che si parla di Trilogia piuttosto che non di — Periodo — come di solito si usano designare le vicendevoli fasi di una ricerca artistica: il processo evolutivo, in questo caso, va per larghe fasi concettuali, ciascuna riassuntiva di una sequenza di strati di coscienza sedimentati nella memoria storica, da un lato, e nella certezza dell’attualità, dall’altro.

Quindi le “zone” di Pezzuco riepilogano un insieme di esperienze umane, il cui elaborato simbolico riemerge nel Presente per fissarsi nel Futuro: di esse permane nell’occhio di chi osserva un tessuto segnico fitto di tratti vicini e ristretti, codificabili secondo il sistema della comunicazione corrente.

L’acrilico su tavola, quest’ultima protetta da lastre di plexiglass, è ancora il modo attuale di esprimersi, contro l’utilizzo pieno ed esclusivo di materiali vari nelle Opere della sua prima vicenda artistica: la pittura procede ad ampie campiture cromatiche che, mosse e dinamiche, distribuiscono le sfaccettature concettuali del Artista su diversi livelli.

L’ipotizzabile intima sutura tra UOMO e NATURA, qui, in queste ultime Opere, trova una conferma diversa in quanto è sottoposta ad una diversa qualificazione interpretativa: il rapporto tra i due concetti basilari della sua poetica si allenta e le fibre che li tengono uniti si dipanano sensibilmente per favorire l’accesso a quegli elementi eterodossi che ne sconvolgono l’equilibrio… in un impietoso atto di denuncia, una denuncia garbata, elegante, raffinata come sono, e sono sempre stati, i suoi modi, ma pur sempre denuncia.

Sagome umane, tracciate con quell’estremismo segnico che caratterizzava la pittura del Duecento, appaiono come congelate all’interno di tasselli di legno (sovrapposti al piano pittorico) che ne esaltano il valore totemico sia sul piano esistenziale sia sul piano comunicazionale… mentre vengono irretite da piccoli segni e figure geometriche, intenti a comporre una maglia di anelli imperforabili piuttosto che un dialogo incisivo e concreto

I segni dell’aria, esattamente come rimanda il titolo di una recente realizzazione: Il Giocoliere dell’Aria, volano via indisturbati… senza lasciare traccia

È il dramma della comunicazione odierna, dove ai VERBA VOLANT si sono sostituiti gli SCRIPTA VOLANT... è il dramma dell’attuale umanità dispersa nello spirito e incapace di confermare nel tempo veri valori, veri sentimenti, vere emozioni…

Ma il tempo va… ugualmente e inesorabilmente va… Cromìe a fascie, accostate con spirito di giustapposizione, si contorcono con moto dinamico sulla superficie dipinta, in senso orizzontale ma anche verticale, indicando l’azione dello stratificare, del sedimentare… che il tempo regolarmente compie, quasi ad occultare le tracce di una civiltà a favore della successiva… in segno di rinnovamento e fiducia.

Il dramma della “non corrispondenza” trova nel colore, negli impasti materici e nell’elaborazione formale degli elementi il suo giusto equilibrio estetico: questo è quel momento raro, ma soprattutto altissimo in cui la Pittura, e la capacità di comunicare attraverso di essa, rendono incredibilmente piacevole e coinvolgente una creazione che invece, con ardito gesto intellettuale, riporta alla responsabilità esistenziale l’umanità tutta

Questo è il momento di definire, se vogliamo, un nuovo concettuale in ambito di ricerca, una nuova posizione mentale, un nuovo pensiero artistico.

Volendo fare il punto della situazione nell’ambito della produzione del Artista, ci troviamo di fronte a tre passaggi espressivi e stilistici ben precisi, che sollecitano di essere messi a fuoco e fissati una volta per tutte: nella prima fase del suo lavoro egli sviluppa un rapporto molto intimo con la MATERIA, tanto da assumerla a protagonista indiscussa dei temi trattati e poiché la tematica, allora come anche oggi, verte sul binomio puro UOMO —NATURA, le componenti materiali utilizzate erano chiamate a rendere esplicito e tangibile il suo Discours sur la Nature perdue par l’homme e per “tangibile” intendo sensibile al tatto, nel senso che si potevano toccare con mano alcune presenze terrene come foglie, sassi, conchiglie, spaghi… il tutto organizzato in ensemble con paste cromatiche su lastre lignee tradotte in contenitori.

Nella seconda fase del suo lavoro l’Artista spinge la sua meditazione a livelli subliminali, al punto che la derivante espressione artistica acquisice leggerezza, impalpabilità, ariosità mentre il sistema segnico si dirada sul piano della comunicazione, che è anche il piano della pittura, in segni liberi, aerei, come fluttuanti nell’infinitezza di un mondo senza confini, mentre il colore si discioglie in tonalità soffici e poetiche, mentre la Materia —Mater (per evocare un concetto boccioniano) si riassorbe in un clima sospeso e atmosferico.

Ma la concettualità, soprattutto se improntata a filosofie dense e ricche di risvolti, oserei dire, psicoanalitici, non è cosa di tutti e questo momento della creatività d Pezzuco, pur alto e caleidoscopico, ha lasciato un segno indelebile nella fruizione pubblica… La revisione che ne è naturalmente scaturita ha originato la trilogia della sua creazione.

Qui l’Artista ristempera i dettati precedenti in un’equilibrio compositivo e pittorico che ha del magico: le dimensioni si sono leggermente ridotte e la superficie della tavola si arricchisce di significazioni segniche che vanno al di là della percezione sensibile, sollecitano lo spettatore ad un diverso godimento… non quello del tattoriale e dell’immediato, ma quello del cerebrale e del meditato.

Una parte di quest’ultima produzione è esposta in spazi inusuali per una mostra d’Arte: non la solita galleria, non la solita sala civica, ma le lussuose stanze di un Albergo: Elaia Garden Hotel che raccoglie, come in una grande personale, numerose opere del Maestro, quasi tutte collocate sulle pareti delle camere a convogliare l’impatto ottico di chi entra nella stanza e definire così le coordinate visive dell’intera scatola spaziale che, inserita in una costruzione modernissima e stilisticamente essenziale, riesce a vivere, attraverso queste opere, una seconda dimensione, trasformandosi in una struttura ponte tra il Pensiero umano e la Natura circostante (terra, mare, aria…), tema centrale del canto pezzuchiano.

Non è da tutti riuscire a creare un aggancio simile all’ambiente naturale, restituendo ad esso l’integrità perduta e il rispetto che merita… molte organizzazioni d’accoglienza turistica, quando decidono di arricchire le proprie collezioni d’Arte, lo fanno in maniera impropria e mistilinea, mentre qui, all’Elaia Garden, sembra si sia seguito un disegno preciso per attuare con i mezzi dell’Architettura e della Pittura un’opera completa come quelle che un tempo gli Artisti erano chiamati a compiere.

Le Opere presenti all’Hotel Elaia fanno parte, come si è detto, della terza sequenza ciclica del Maestro, alla quale peraltro appartengono anche molte altre composizioni realizzate recentemente ed è in tal senso che si parla di Trilogia piuttosto che non di — Periodo — come di solito si usano designare le vicendevoli fasi di una ricerca artistica: il processo evolutivo, in questo caso, va per larghe fasi concettuali, ciascuna riassuntiva di una sequenza di strati di coscienza sedimentati nella memoria storica, da un lato, e nella certezza dell’attualità, dall’altro.

Quindi le “zone” di Pezzuco riepilogano un insieme di esperienze umane, il cui elaborato simbolico riemerge nel Presente per fissarsi nel Futuro: di esse permane nell’occhio di chi osserva un tessuto segnico fitto di tratti vicini e ristretti, codificabili secondo il sistema della comunicazione corrente.

L’acrilico su tavola, quest’ultima protetta da lastre di plexiglass, è ancora il modo attuale di esprimersi, contro l’utilizzo pieno ed esclusivo di materiali vari nelle Opere della sua prima vicenda artistica: la pittura procede ad ampie campiture cromatiche che, mosse e dinamiche, distribuiscono le sfaccettature concettuali del Artista su diversi livelli.

L’ipotizzabile intima sutura tra UOMO e NATURA, qui, in queste ultime Opere, trova una conferma diversa in quanto è sottoposta ad una diversa qualificazione interpretativa: il rapporto tra i due concetti basilari della sua poetica si allenta e le fibre che li tengono uniti si dipanano sensibilmente per favorire l’accesso a quegli elementi eterodossi che ne sconvolgono l’equilibrio… in un impietoso atto di denuncia, una denuncia garbata, elegante, raffinata come sono, e sono sempre stati, i suoi modi, ma pur sempre denuncia.

Sagome umane, tracciate con quell’estremismo segnico che caratterizzava la pittura del Duecento, appaiono come congelate all’interno di tasselli di legno (sovrapposti al piano pittorico) che ne esaltano il valore totemico sia sul piano esistenziale sia sul piano comunicazionale… mentre vengono irretite da piccoli segni e figure geometriche, intenti a comporre una maglia di anelli imperforabili piuttosto che un dialogo incisivo e concreto

I segni dell’aria, esattamente come rimanda il titolo di una recente realizzazione: Il Giocoliere dell’Aria, volano via indisturbati… senza lasciare traccia

È il dramma della comunicazione odierna, dove ai VERBA VOLANT si sono sostituiti gli SCRIPTA VOLANT... è il dramma dell’attuale umanità dispersa nello spirito e incapace di confermare nel tempo veri valori, veri sentimenti, vere emozioni…

Ma il tempo va… ugualmente e inesorabilmente va… Cromìe a fascie, accostate con spirito di giustapposizione, si contorcono con moto dinamico sulla superficie dipinta, in senso orizzontale ma anche verticale, indicando l’azione dello stratificare, del sedimentare… che il tempo regolarmente compie, quasi ad occultare le tracce di una civiltà a favore della successiva… in segno di rinnovamento e fiducia.

Il dramma della “non corrispondenza” trova nel colore, negli impasti materici e nell’elaborazione formale degli elementi il suo giusto equilibrio estetico: questo è quel momento raro, ma soprattutto altissimo in cui la Pittura, e la capacità di comunicare attraverso di essa, rendono incredibilmente piacevole e coinvolgente una creazione che invece, con ardito gesto intellettuale, riporta alla responsabilità esistenziale l’umanità tutta

Questo è il momento di definire, se vogliamo, un nuovo concettuale in ambito di ricerca, una nuova posizione mentale, un nuovo pensiero artistico.

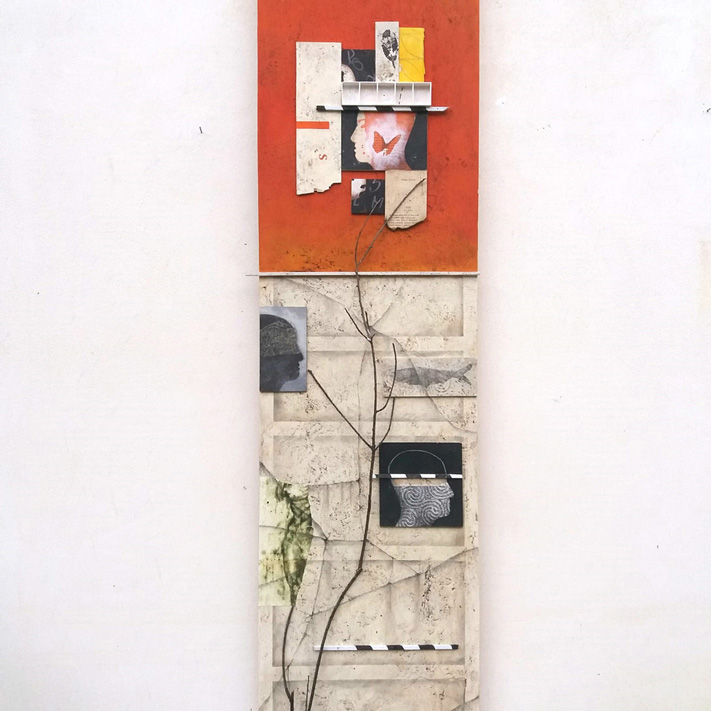

frammenti diversi

"carte scoperte"

"carte scoperte"

L’invisibile e il tangibile

Vera Pitzalis

“We can communicate with the earth, the earth is alive,

the earth can talk to us, we just have to listen…. we have the means… the earth lends itself to our comprehension, calls to us so that we may listen”

(J. Beuys)

the earth can talk to us, we just have to listen…. we have the means… the earth lends itself to our comprehension, calls to us so that we may listen”

(J. Beuys)

Rectangular boards 50 x 125 cm in mixed technique hang before our eyes in an apparently fathomless crypticity...

A vertical one – which would seem to correspond to the “philosophical boundary” to which Francesco Pezzuco alludes in a brief introductory caption – divides each work into two equivalent parts: the left hand side appears populated with an alpha-numerical succession, while the right hand side destabilizes the viewer with an initial white neutrality. Then, a series of hyphens, signs, invite us to play and to embrace the work not only in a sensorial way, pre-cognitively, but also intellectually, allowing us to discover its name. The latter is revealed to us, together with the right hand side of the work, in a progressive and surprising way, functioning as with a magic lantern, through the pressing of numbers on the left hand side: we are therefore authorized by the artist to a direct involvement in the completion of the artistic process, which leaves us questioning and hopeful for answers. The mechanism functioning in Pezzuco’s latest work - grouped under the paradigmatic title of “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile”- is, in my opinion, subtly and exquisitely philosophical. Evoking the theory of opposites already hypothesized by Pythagoras, the pre-Socratic and other schools of philosophy, this mechanism reveals (like a modern Pandora’s box) the organic and inextricable nature of reality, made up of incongruous entities such as the visible and the intelligible on the one hand and the invisible, the mysterious on the other. I also think that one should not underestimate the term chosen by the artist, preferring ‘tangible’ to the more predictable and inflated ‘visible’: a preference which confirms the irruption of touch in the pressing of numbers but which also, on a more profound conceptual level, rehabilitates the role of this sense into artistic practice, now that the hypertrophy of the visual is all-prevailing. The sense of touch had been considered, by French and German philosophers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, vehicle of the sublime and therefore of reality brought to the its utmost revelation, and beyond comparison with the simple visual registration of natural phenomena and non.

But let us return to our former discussion on the existence of opposites, as much in the world as in the latest work of Francesco Pezzuco. The first concept, that is the “visible”, is conveyed by the artist with the alpha-numeric surface previously mentioned, which collects all the logical, conventional coordinates for the discovery of the initial “invisible” which assails us in the other half of the work, before we are drawn to participate in the artist’s ludus . But actually, the “invisible” – borrowing Merleau Ponty’s sybilline words – “is that fabric which lines the visible, upholds it, nurtures it and is in itself, not ‘thing’ but possibility, latency and the flesh of things”. The invisible is the nourishment of reality just as much as is the visible, as is that which can be experienced by all five senses: both are legitimate threads of the dense matrix called experience, reality. Without it, being arcane and powerful knowledge, the “tangible” in things cannot be determined. But this idea is two way, as it is true that opposites can give shape to shades, to degrees of possibility, all equally valid in the world. Such possibilities, which go from the solicitation of the numbers to the identification of fragments of images, combining as for a puzzle in the panels on the right hand side, lead to the solution of the rebus which is in fact the work’s name. The latter, too often underestimated even by the experts when first experiencing a work of art, here plays a fundamental role which is indicative of the philosophical strains mentioned above. And what can we say about those eggs, those moons, those figures of trees, butterflies and parts of the human body which connotate Pezzuco’s iconographic repertoire and which we have seen fitted into an organized geometric matrix throughout his preceding pictorial series?! His own words in the preface to “L’invisibile e il Tangibile” seem to describe these elements as establishing an aesthetic convergence between two other polarities which make up reality: the macroscopic – exemplified by Leonardo type sketches of anatomy or by photographic negative type trees dirtied with colour – and the microscopic – rendered visible by unexpected enlargements, not immediately apparent, as for “Amazzonia Day” -. But this unfolding of figures, so tuned and combined, bring up another fundamental dyad from which stem the works of the years 2008 and 2010, in particular “COGNIZIONI IPC” and “ESTENSIONE ORIZZONTALE”: that is the coupling of the analytical with the synthetic in viewing reality, at one time both intellectual and sensorial. The weight of the first transpires unequivocally through the constructs of weight systems, of vectors, of orthogonal projections and of solid geometric shapes placed outside the borders of the paintings and of specific compositions; the second, the more perceptive, anthropocentric component, emerges through several elements: through two constants – saturated colour and images of human anatomy, through the use of brief strokes which evoke ancient rock paintings or inscriptions, or through lines of scientific precision, belonging to the illustrator of medical books or to the miniaturist (see “Corpo Progetto”, part of the corpus of “L’invisibile e il tangibile”).

What is the evolutionary path of this iconography and what is its symbolic load, seen in the light of a prolific and eclectic career such as that of Francesco Pezzuco? The former starts with the motions of an informal, material pictorial work which, as suggested by the series of works entitled “Organika” in 2004, is enriched by objects taken from the natural world, brought to a second life: here appear, particularly in reference to the works of the years 2004-2006, the wooden flotsam sculpted by the sea, which serve as “symbolic metonyms” of all that is Nature (Physis), re-collocated to that centrality from where mechanization and mass society have banished it. Alongside these, arise the anthropomorphic shapes and again heads accompanied by numbers and birds, all invested by a dense matrix of signs of ancestral memory, also evoked by the recurring cosmic egg and moon which stand for the fascination of the artist for mysticism and cosmology. If we also make a further consideration – supported by Pezzuco himself with his “Omaggio a J.Beuys” (2006) and by the contributions of other critics before mine -, that is, his strong admiration for this German avant-garde artist, then the composite mosaic of his work acquires a surprising coherence and clear ethical vocation. But why so, will a curious reader wonder? Because everything that has been discussed concerning Francesco Pezzuco (regarding the relationship between the visible and invisible ,the material and immaterial, regarding the totemic function of certain natural elements reconfigured in an artistic view, regarding nature and man and its implications for ecology, regarding the quest for an ancestral and absolute harmony), has had its seismic epicenter in Beuys, dubbed by the contemporary press as the “Shaman of Art” ( the famous performance of May 1974 “I like America and America likes me” suffices to explain the label). A Shaman, in that he reproduced – not through paintings but through cathartic and irreverent performances – the mystic tension between the polarities of the world, pushing spectators to be responsible and become aware of their social and anthropological status.

The work of Francesco Pezzuco is, in my opinion, conveyor of this philosophy which tends to an organic re-composition of dualisms internal and external to man, but also to a explication of those mechanisms which uphold man’s perception of the world and of which this latest corpus of work, “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile”, is a paradigm, oscillating between the archetypical and the analytical: a Panic immersion into the world across the surface or ‘skin’ of each work, a privileged portal of access out of all time.

But let us return to our former discussion on the existence of opposites, as much in the world as in the latest work of Francesco Pezzuco. The first concept, that is the “visible”, is conveyed by the artist with the alpha-numeric surface previously mentioned, which collects all the logical, conventional coordinates for the discovery of the initial “invisible” which assails us in the other half of the work, before we are drawn to participate in the artist’s ludus . But actually, the “invisible” – borrowing Merleau Ponty’s sybilline words – “is that fabric which lines the visible, upholds it, nurtures it and is in itself, not ‘thing’ but possibility, latency and the flesh of things”. The invisible is the nourishment of reality just as much as is the visible, as is that which can be experienced by all five senses: both are legitimate threads of the dense matrix called experience, reality. Without it, being arcane and powerful knowledge, the “tangible” in things cannot be determined. But this idea is two way, as it is true that opposites can give shape to shades, to degrees of possibility, all equally valid in the world. Such possibilities, which go from the solicitation of the numbers to the identification of fragments of images, combining as for a puzzle in the panels on the right hand side, lead to the solution of the rebus which is in fact the work’s name. The latter, too often underestimated even by the experts when first experiencing a work of art, here plays a fundamental role which is indicative of the philosophical strains mentioned above. And what can we say about those eggs, those moons, those figures of trees, butterflies and parts of the human body which connotate Pezzuco’s iconographic repertoire and which we have seen fitted into an organized geometric matrix throughout his preceding pictorial series?! His own words in the preface to “L’invisibile e il Tangibile” seem to describe these elements as establishing an aesthetic convergence between two other polarities which make up reality: the macroscopic – exemplified by Leonardo type sketches of anatomy or by photographic negative type trees dirtied with colour – and the microscopic – rendered visible by unexpected enlargements, not immediately apparent, as for “Amazzonia Day” -. But this unfolding of figures, so tuned and combined, bring up another fundamental dyad from which stem the works of the years 2008 and 2010, in particular “COGNIZIONI IPC” and “ESTENSIONE ORIZZONTALE”: that is the coupling of the analytical with the synthetic in viewing reality, at one time both intellectual and sensorial. The weight of the first transpires unequivocally through the constructs of weight systems, of vectors, of orthogonal projections and of solid geometric shapes placed outside the borders of the paintings and of specific compositions; the second, the more perceptive, anthropocentric component, emerges through several elements: through two constants – saturated colour and images of human anatomy, through the use of brief strokes which evoke ancient rock paintings or inscriptions, or through lines of scientific precision, belonging to the illustrator of medical books or to the miniaturist (see “Corpo Progetto”, part of the corpus of “L’invisibile e il tangibile”).

What is the evolutionary path of this iconography and what is its symbolic load, seen in the light of a prolific and eclectic career such as that of Francesco Pezzuco? The former starts with the motions of an informal, material pictorial work which, as suggested by the series of works entitled “Organika” in 2004, is enriched by objects taken from the natural world, brought to a second life: here appear, particularly in reference to the works of the years 2004-2006, the wooden flotsam sculpted by the sea, which serve as “symbolic metonyms” of all that is Nature (Physis), re-collocated to that centrality from where mechanization and mass society have banished it. Alongside these, arise the anthropomorphic shapes and again heads accompanied by numbers and birds, all invested by a dense matrix of signs of ancestral memory, also evoked by the recurring cosmic egg and moon which stand for the fascination of the artist for mysticism and cosmology. If we also make a further consideration – supported by Pezzuco himself with his “Omaggio a J.Beuys” (2006) and by the contributions of other critics before mine -, that is, his strong admiration for this German avant-garde artist, then the composite mosaic of his work acquires a surprising coherence and clear ethical vocation. But why so, will a curious reader wonder? Because everything that has been discussed concerning Francesco Pezzuco (regarding the relationship between the visible and invisible ,the material and immaterial, regarding the totemic function of certain natural elements reconfigured in an artistic view, regarding nature and man and its implications for ecology, regarding the quest for an ancestral and absolute harmony), has had its seismic epicenter in Beuys, dubbed by the contemporary press as the “Shaman of Art” ( the famous performance of May 1974 “I like America and America likes me” suffices to explain the label). A Shaman, in that he reproduced – not through paintings but through cathartic and irreverent performances – the mystic tension between the polarities of the world, pushing spectators to be responsible and become aware of their social and anthropological status.

The work of Francesco Pezzuco is, in my opinion, conveyor of this philosophy which tends to an organic re-composition of dualisms internal and external to man, but also to a explication of those mechanisms which uphold man’s perception of the world and of which this latest corpus of work, “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile”, is a paradigm, oscillating between the archetypical and the analytical: a Panic immersion into the world across the surface or ‘skin’ of each work, a privileged portal of access out of all time.

“Noi possiamo comunicare con la terra, la terra è viva, la terra può parlarci, basta cominciare ad ascoltare... gli strumenti li abbiamo... la terra si offre alla nostra comprensione, ci chiama perché noi ci prestiamo all’ascolto”.

(J. Beuys)

(J. Beuys)

Rettangoli di 50x25 cm in tecnica mista su tavola si stagliano davanti ai nostri occhi in una apparentemente insondabile cripticità...

Una verticale - che sembrerebbe corrispondere al “confine filosofico” cui allude l’artista Francesco Pezzuco nella breve didascalia a questo suo corpus di opere - ripartisce ciascuno di essi in due superfici equivalenti: quella sinistra appare popolata da una successione alfanumerica, mentre quella destra destabilizza il fruitore con la sua iniziale neutralità bianca. Ma poi ecco una sequenza di trattini che, invitandoci al gioco e ad una conquista non solo sensoriale e precognitiva dell’opera ma anche intellettuale, lasciano intuire la presenza di un titolo. Quest’ultimo si rivela a noi, assieme alla porzione destra del quadro, in maniera progressiva e sorprendente come in una lanterna magica, attraverso la pigiatura dei numeretti siti nella superficie sinistra: siamo quindi autorizzati dall’artista ad una intromissione diretta nel compiersi del processo artistico, che suscita in noi uno sguardo benevolmente interrogativo e famelico di risposte. Il meccanismo a cui le ultime opere di Pezzuco - raccolte sotto il titolo paradigmatico di “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile” - soggiacciono è, a mio avviso, sottilmente e squisitamente filosofico. Lo è nella misura in cui, richiamandosi alla teoria degli opposti già postulata da Pitagora, i presocratici e da successive scuole filosofiche, rivela (come un moderno vaso di Pandora) la natura organica e inestricabile della realtà, fatta di entità antinomiche come il visibile e l’intelligibile da una parte e l’invisibile, il misterioso dall’altra. Credo poi non sia da sottovalutare la preferenza accordata dall’artista al termine “tangibile” piuttosto che al ben più prevedibile e inflazionato “visibile”: favore, questo, che conferma certamente l’irruzione del tatto nell’operazione di pigiatura dei numeretti ma che riabilita anche, ad un livello concettuale più profondo, il ruolo di questo senso nella prassi artistica a fronte di una ipertrofia visiva oramai imperante. Un senso quello del tatto che, per i filosofi francesi e tedeschi del Settecento e dell’Ottocento, era veicolo del sublime e quindi di una realtà potenziata all’ennesimo livello rispetto alla semplice registrazione visiva dei fenomeni naturali e non.

Ma torniamo al discorso precedentemente enunciato sugli opposti che sostanziano tanto il mondo quanto, nello specifico, le ultime opere di Francesco Pezzuco.

Al primo dei concetti enunciati, ossia il “visibile”, l’artista fa corrispondere la superficie alfanumerica precedentemente ricordata, che raccoglie le coordinate logiche, convenzionali per la scoperta dell’”invisibile” iniziale da cui siamo assaliti nell’altra metà dell’opera, prima che ci accingiamo ad assecondare il ludus dell’autore. Ma, a ben vedere, questo “invisibile” è - prendendo a prestito le parole sibilline di Merleau Ponty - “quel tessuto che fodera il visibile, lo sostiene, lo alimenta e che, dal canto suo, non è cosa, ma possibilità, latenza e carne delle cose”. L’invisibile è nutrimento del reale tanto quanto ciò che è visibile, esperibile attraverso tutti e cinque i nostri sensi: entrambi sono i fili legittimi di un fitto ordito chiamato esperienza, realtà. Senza di esso, che è arcano e conoscenza in potenza, non è possibile determinare la “tangibilità” delle cose. Ma il discorso ha validità biunivoca d’altro canto, se è vero che gli opposti danno corpo alle sfumature, alle possibilità diverse e tutte ugualmente valide del mondo. Tali possibilità, che passano per la sollecitazione dei numeretti e l’identificazione dei lacerti di immagini che si vengono componendo come un puzzle nella porzione destra dei pannelli, conducono alla risoluzione del rebus in cui di fatto consiste il titolo. Quest’ultimo, troppo spesso sottovalutato da addetti ai lavori e non in un primo accostamento ad una qualsivoglia opera d’arte, riveste qui un molo fondamentale e indicativo del sostrato filosofico che ho argomentato poco sopra. Che dire poi di quelle

uova, di quelle lune, di quelle sagome di alberi, di farfalle e di parti anatomiche umane che connotano in senso stretto il suo repertorio iconografico e che vediamo rigidamente incasellate entro una inappuntabile partitura geometrica fin dalle precedenti serie pittoriche dell’artista?! Come lascerebbero presagire le sue stesse parole nella prefazione a “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile”, esse sanciscono l’incontro e(s)tetico tra altre due polarità costitutive della nostra realtà: il macroscopico - esemplificato dagli schizzi anatomici di sapore leonardesco o dalle sagome d’albero rese come in un negativo fotografico sporcato di colore - e il microscopico - reso visibile attraverso degli ingrandimenti stranianti e non sempre di immediata leggibilità, come attesta “Amazzonia Day” -. Ma questo dispiegamento di figure, così declinato e combinato, fa affiorare un’altra diade fondamentale di cui sono chiara estrinsecazione soprattutto le opere del 2008 e del 2010, con particolare riferimento a “COGNIZIONI IPC” ed “ESTENS10NE ORIZZONTALE”: quella formata da uno sguardo assieme analitico e sintetico alla realtà, ad un tempo intellettuale e sensoriale. Il peso del

primo traspare inequivocabilmente dal sistema di pesi, di linee vettoriali, proiezioni ortogonali e di solidi geometrici costruiti rispettivamente attorno alla sagoma dei quadri e a determinati elementi compositivi; la componente più smaccatamente percettiva e antropocentrica emerge nell’impiego continuativo di colori saturi e dalla costante dell’anatomia umana, variamente delineata: o con il tratto sintetico che rievoca antiche pitture rupestri e incisioni antiche, o con la precisione scientifica di un illustratore di libri di medicina ma anche di un miniaturista (si osservi “Corpo Progetto”, appartenente al corpus “L’Invisibile e il tangibile”).

Quale il percorso evolutivo di questa iconografia e quale il suo carico simbolico, alla luce di una carriera prolifica e quantomai eclettica come quella di Francesco Pezzuco? Il primo muove dalle premesse di una pittura informale materica che, come suggerisce un’importante serie di opere quale “Organika” del 2004, si arricchisce di oggetti prelevati dal mondo naturale e riconsegnati ad una seconda vita: ecco quindi apparire, specie in rapporto ai lavori del biennio 2004-2006, i ben noti rami levigati dal mare, che assurgono a “metonimie simboliche” di quel tutto che è la Natura (Physis), ricollocata in una meritata centralità da cui meccanizzazione e società di massa l’hanno quasi del tutto estromessa. Affianco ad essi, balenano le sagome antropomorfe e le teste profilate accompagnate da numeri e volatili e investite da una fitta trama segnica di ancestrale memoria, così come pure la evocativa ricorrenza dell’uovo cosmico e della luna, referenti di una forte fascinazione dell’artista per il misticismo e la cosmologia. Se accanto a queste considerazioni ne operiamo una ulteriore - peraltro corroborata dallo stesso Pezzuco con il suo “Omaggio a J Beuys” (2006) e da altri contributi critici anteriori al mio -, relativa al forte apprezzamento per l’artista tedesco

delle Neo-avanguardie, il mosaico composito della sua poetica acquisisce una sorprendente coerenza e una altrettanto chiara vocazione etica. E perché mai, si domanderà il lettore avveduto e incuriosito? Perché quanto finora argomentato per l’artista laziale (nel merito dei rapporti tra visibile e invisibile, materiale e immateriale, funzione totemica di alcuni elementi naturali riconfigurati in chiave artistica, riflessione sul rapporto tra uomo e natura e conseguenti implicazioni ecologiche, ricerca di un’armonia ancestrale e assoluta), ha avuto il suo epicentro sismico proprio in Beuys, soprannominato dalla stampa del suo tempo “lo sciamano dell’arte” (basti richiamarsi, per esempio, alla celebre performance del maggio 1974 “I like America and America likes me”, per comprenderne le ragioni). Sciamano nella misura in cui ha fatto rivivere - attraverso non dei quadri ma delle performance piuttosto dissacranti e catartiche - la tensione mistica tra le polarità del mondo, invitando i fruitori ad auto-responsabilizzarsi e a prendere coscienza del proprio status sociale e antropologico.

Anche le opere di Francesco Pezzuco sono, a mio avviso, latrici di questa filosofia tesa alla ricomposizione organica ·dei dualismi interni ed esterni all’uomo, ma anche allo squadernamento di quei meccanismi che ne presiedono la percezione del mondo e di cui proprio l’ultimo corpus, “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile”, è paradigma oscillante tra l’archetipico e l’analitico: un’immersione panica nel mondo che ha nella ‘pelle’ delle tavole una porta di accesso privilegiata e senza tempo.

Ma torniamo al discorso precedentemente enunciato sugli opposti che sostanziano tanto il mondo quanto, nello specifico, le ultime opere di Francesco Pezzuco.

Al primo dei concetti enunciati, ossia il “visibile”, l’artista fa corrispondere la superficie alfanumerica precedentemente ricordata, che raccoglie le coordinate logiche, convenzionali per la scoperta dell’”invisibile” iniziale da cui siamo assaliti nell’altra metà dell’opera, prima che ci accingiamo ad assecondare il ludus dell’autore. Ma, a ben vedere, questo “invisibile” è - prendendo a prestito le parole sibilline di Merleau Ponty - “quel tessuto che fodera il visibile, lo sostiene, lo alimenta e che, dal canto suo, non è cosa, ma possibilità, latenza e carne delle cose”. L’invisibile è nutrimento del reale tanto quanto ciò che è visibile, esperibile attraverso tutti e cinque i nostri sensi: entrambi sono i fili legittimi di un fitto ordito chiamato esperienza, realtà. Senza di esso, che è arcano e conoscenza in potenza, non è possibile determinare la “tangibilità” delle cose. Ma il discorso ha validità biunivoca d’altro canto, se è vero che gli opposti danno corpo alle sfumature, alle possibilità diverse e tutte ugualmente valide del mondo. Tali possibilità, che passano per la sollecitazione dei numeretti e l’identificazione dei lacerti di immagini che si vengono componendo come un puzzle nella porzione destra dei pannelli, conducono alla risoluzione del rebus in cui di fatto consiste il titolo. Quest’ultimo, troppo spesso sottovalutato da addetti ai lavori e non in un primo accostamento ad una qualsivoglia opera d’arte, riveste qui un molo fondamentale e indicativo del sostrato filosofico che ho argomentato poco sopra. Che dire poi di quelle

uova, di quelle lune, di quelle sagome di alberi, di farfalle e di parti anatomiche umane che connotano in senso stretto il suo repertorio iconografico e che vediamo rigidamente incasellate entro una inappuntabile partitura geometrica fin dalle precedenti serie pittoriche dell’artista?! Come lascerebbero presagire le sue stesse parole nella prefazione a “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile”, esse sanciscono l’incontro e(s)tetico tra altre due polarità costitutive della nostra realtà: il macroscopico - esemplificato dagli schizzi anatomici di sapore leonardesco o dalle sagome d’albero rese come in un negativo fotografico sporcato di colore - e il microscopico - reso visibile attraverso degli ingrandimenti stranianti e non sempre di immediata leggibilità, come attesta “Amazzonia Day” -. Ma questo dispiegamento di figure, così declinato e combinato, fa affiorare un’altra diade fondamentale di cui sono chiara estrinsecazione soprattutto le opere del 2008 e del 2010, con particolare riferimento a “COGNIZIONI IPC” ed “ESTENS10NE ORIZZONTALE”: quella formata da uno sguardo assieme analitico e sintetico alla realtà, ad un tempo intellettuale e sensoriale. Il peso del

primo traspare inequivocabilmente dal sistema di pesi, di linee vettoriali, proiezioni ortogonali e di solidi geometrici costruiti rispettivamente attorno alla sagoma dei quadri e a determinati elementi compositivi; la componente più smaccatamente percettiva e antropocentrica emerge nell’impiego continuativo di colori saturi e dalla costante dell’anatomia umana, variamente delineata: o con il tratto sintetico che rievoca antiche pitture rupestri e incisioni antiche, o con la precisione scientifica di un illustratore di libri di medicina ma anche di un miniaturista (si osservi “Corpo Progetto”, appartenente al corpus “L’Invisibile e il tangibile”).

Quale il percorso evolutivo di questa iconografia e quale il suo carico simbolico, alla luce di una carriera prolifica e quantomai eclettica come quella di Francesco Pezzuco? Il primo muove dalle premesse di una pittura informale materica che, come suggerisce un’importante serie di opere quale “Organika” del 2004, si arricchisce di oggetti prelevati dal mondo naturale e riconsegnati ad una seconda vita: ecco quindi apparire, specie in rapporto ai lavori del biennio 2004-2006, i ben noti rami levigati dal mare, che assurgono a “metonimie simboliche” di quel tutto che è la Natura (Physis), ricollocata in una meritata centralità da cui meccanizzazione e società di massa l’hanno quasi del tutto estromessa. Affianco ad essi, balenano le sagome antropomorfe e le teste profilate accompagnate da numeri e volatili e investite da una fitta trama segnica di ancestrale memoria, così come pure la evocativa ricorrenza dell’uovo cosmico e della luna, referenti di una forte fascinazione dell’artista per il misticismo e la cosmologia. Se accanto a queste considerazioni ne operiamo una ulteriore - peraltro corroborata dallo stesso Pezzuco con il suo “Omaggio a J Beuys” (2006) e da altri contributi critici anteriori al mio -, relativa al forte apprezzamento per l’artista tedesco

delle Neo-avanguardie, il mosaico composito della sua poetica acquisisce una sorprendente coerenza e una altrettanto chiara vocazione etica. E perché mai, si domanderà il lettore avveduto e incuriosito? Perché quanto finora argomentato per l’artista laziale (nel merito dei rapporti tra visibile e invisibile, materiale e immateriale, funzione totemica di alcuni elementi naturali riconfigurati in chiave artistica, riflessione sul rapporto tra uomo e natura e conseguenti implicazioni ecologiche, ricerca di un’armonia ancestrale e assoluta), ha avuto il suo epicentro sismico proprio in Beuys, soprannominato dalla stampa del suo tempo “lo sciamano dell’arte” (basti richiamarsi, per esempio, alla celebre performance del maggio 1974 “I like America and America likes me”, per comprenderne le ragioni). Sciamano nella misura in cui ha fatto rivivere - attraverso non dei quadri ma delle performance piuttosto dissacranti e catartiche - la tensione mistica tra le polarità del mondo, invitando i fruitori ad auto-responsabilizzarsi e a prendere coscienza del proprio status sociale e antropologico.

Anche le opere di Francesco Pezzuco sono, a mio avviso, latrici di questa filosofia tesa alla ricomposizione organica ·dei dualismi interni ed esterni all’uomo, ma anche allo squadernamento di quei meccanismi che ne presiedono la percezione del mondo e di cui proprio l’ultimo corpus, “L’Invisibile e il Tangibile”, è paradigma oscillante tra l’archetipico e l’analitico: un’immersione panica nel mondo che ha nella ‘pelle’ delle tavole una porta di accesso privilegiata e senza tempo.

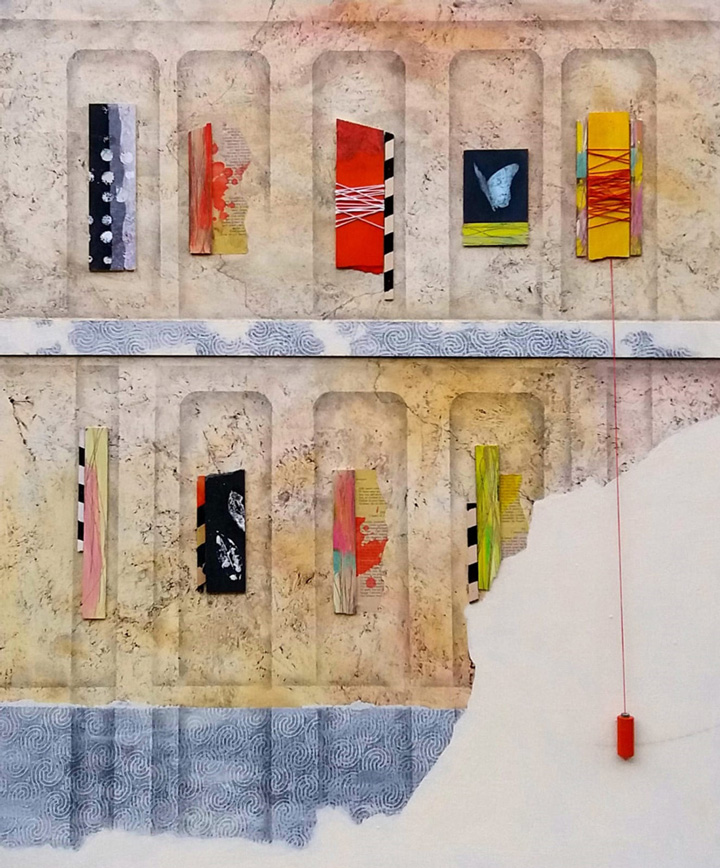

frammenti diversi

"Humanitas"

polimaterico su legno cm. 140x130

"Humanitas"

polimaterico su legno cm. 140x130

Paradossi visibili

Anna Mola

“Anxiety caused by uncertainty

Is the raw material that makes society fertile

Individualized for consumer purposes.”

by: “Society under Siege” Zygmunt Bauman

Is the raw material that makes society fertile

Individualized for consumer purposes.”

by: “Society under Siege” Zygmunt Bauman

The artworks that I will analyze are the continuation of the series “L’invisibile e il Tangibile” (“The Invisible and the Tangible”) and were realized between 2016 and 2017...

The first difference - in my opinion, fundamental - compared to the works previously created is the change of dimensions: from narrow vertical panels, becoming “strips” in some cases, to horizontal rectangles, much more proportional, finally arriving to the square form.

Reasons of this different “framing” (to use a proper term of photographic art) can be many: there may be a will - conscious or unconscious - to infuse a greater sense of equilibrium and familiarity into the user and perhaps in the author himself.

By hypothesizing, we can think of a correspondence between the new physical dimensions of the paintings, a renewed approach to their subjects and further an approach to a certain kind of realism. Subjects that I’m going to analyze now.

The division of the table in several areas, the search for basic geometric shapes (such as the line and the circle), the sketching of human and natural figures and the insertion of mathematical letters and symbols are constant elements in Pezzuco’s artistic research: his signature. Each of them, however, is rephrased and re-proposed.

The circle first: from a simple hole and opening becomes much larger, until cover ¾ of the total surface. Its definitive transformation is in cosmic form, as evidenced by “Nexus T2/1”, “Nexus T2/2” and “ Elogio delle apparenze” (“Praise of Appearances”). In these artworks, it is possible to observe a geoid sprinkled on imaginary continents, suspended in black void and doubled - in “Nexus T2/2” - in its possible corresponding mathematical formula.

Even the lines change, always comparing with the previous works, and now divide the space into compartments and sub-compartments, forming striped panels comparable to woody veins (see “Corpoprogetto/1” (Body-project/1). In real wood are the sprigs painted and then applied on the surface; they make the painting more material. We can observe them in “Nature and Psyche” (2 and 3).

But it is in the figurative part of Pezzuco that I trace the greatest development in the artistic phases of the painter. Infact, if until now the human or animal figure is simply a cutout, hatching, “parietal” engraving, now it acquires thickness and three-dimensionality, in order to establish a dialectical relationship, how we can see in both “Nature and Psyche/1” and “Nature and Psyche/2”.

The theme of the “invisible and tangible” acquires, then, new meanings. We see the depicted faces in dialogic connection between them, at least apparently. Pezzuco puts these anonymous subjects – completely decontextualized – one in front of the other but he represents them bandaged, giving rise to what is perfectly expressed in the title: a “Paradox of Visibility”.

Following the sociological analysis of contemporary society, which has as founder and exemplary exponent the researcher Zygmunt Bauman: social relations are more and more labile, uncertain, subject to sudden changes, but in the face of an increasing desire to make themselves “visible” (which Is obviously not synonymous for “true”) and of an equally growing and illusory pretense of knowing and controlling the surrounding world. A paradox is triggered in this sense, perfectly legible in this cycle of artworks, between the necessity of humans to connect with your own (Aristotle defined man as a “social animal”), the obsession – much more recently – to be present and notable in some way, and ultimately the discomforting inability to observe the other one and to be watched profoundly and consciously.

Reasons of this different “framing” (to use a proper term of photographic art) can be many: there may be a will - conscious or unconscious - to infuse a greater sense of equilibrium and familiarity into the user and perhaps in the author himself.

By hypothesizing, we can think of a correspondence between the new physical dimensions of the paintings, a renewed approach to their subjects and further an approach to a certain kind of realism. Subjects that I’m going to analyze now.

The division of the table in several areas, the search for basic geometric shapes (such as the line and the circle), the sketching of human and natural figures and the insertion of mathematical letters and symbols are constant elements in Pezzuco’s artistic research: his signature. Each of them, however, is rephrased and re-proposed.

The circle first: from a simple hole and opening becomes much larger, until cover ¾ of the total surface. Its definitive transformation is in cosmic form, as evidenced by “Nexus T2/1”, “Nexus T2/2” and “ Elogio delle apparenze” (“Praise of Appearances”). In these artworks, it is possible to observe a geoid sprinkled on imaginary continents, suspended in black void and doubled - in “Nexus T2/2” - in its possible corresponding mathematical formula.

Even the lines change, always comparing with the previous works, and now divide the space into compartments and sub-compartments, forming striped panels comparable to woody veins (see “Corpoprogetto/1” (Body-project/1). In real wood are the sprigs painted and then applied on the surface; they make the painting more material. We can observe them in “Nature and Psyche” (2 and 3).

But it is in the figurative part of Pezzuco that I trace the greatest development in the artistic phases of the painter. Infact, if until now the human or animal figure is simply a cutout, hatching, “parietal” engraving, now it acquires thickness and three-dimensionality, in order to establish a dialectical relationship, how we can see in both “Nature and Psyche/1” and “Nature and Psyche/2”.

The theme of the “invisible and tangible” acquires, then, new meanings. We see the depicted faces in dialogic connection between them, at least apparently. Pezzuco puts these anonymous subjects – completely decontextualized – one in front of the other but he represents them bandaged, giving rise to what is perfectly expressed in the title: a “Paradox of Visibility”.

Following the sociological analysis of contemporary society, which has as founder and exemplary exponent the researcher Zygmunt Bauman: social relations are more and more labile, uncertain, subject to sudden changes, but in the face of an increasing desire to make themselves “visible” (which Is obviously not synonymous for “true”) and of an equally growing and illusory pretense of knowing and controlling the surrounding world. A paradox is triggered in this sense, perfectly legible in this cycle of artworks, between the necessity of humans to connect with your own (Aristotle defined man as a “social animal”), the obsession – much more recently – to be present and notable in some way, and ultimately the discomforting inability to observe the other one and to be watched profoundly and consciously.

“L’ansia generata dall’incertezza

è la materia prima che rende fertile la società

individualizzata a scopi di consumo.”

da: “La società sotto assedio” di Zygmunt Bauman

è la materia prima che rende fertile la società

individualizzata a scopi di consumo.”

da: “La società sotto assedio” di Zygmunt Bauman

Le opere che analizzerò sono la continuazione della serie “L'invisibile e il tangibile” e sono state realizzate tra il 2016 e il 2017.

La prima differenza riscontrabile...

La prima differenza riscontrabile...

– a mio avviso fondamentale – rispetto alle opere precedentemente create è il cambio di dimensioni: da pannelli verticali piuttosto stretti, al punto da diventare “strisce”, si passa a rettangoli orizzontali molto più proporzionati, fino ad arrivare alla forma quadrata.

I motivi di questo cambiamento di “inquadratura” (usando un termine proprio dell’arte fotografica) possono essere molteplici: potrebbe esserci una volontà – conscia o inconscia – a infondere un maggior senso di equilibrio, di familiarità volendo, nel fruitore e forse nell’autore stesso.

Ipotizzando, si può pensare a una corrispondenza tra le nuove dimensioni fisiche dell’opera e un rinnovato approccio verso i soggetti delle stesse e a quello che io definirei un avvicinamento a un certo tipo di realismo. Soggetti che ora andrò ad analizzare.

La divisione della tavola in più zone, la ricerca sulle forme geometriche di base (come la linea e il cerchio), l’abbozzo di figure umane e naturali e l’inserimento di lettere e simboli matematici sono elementi costanti nella ricerca artistica di Pezzuco, la sua firma. Ciascuno di essi viene però riformulato e riproposto.

Il cerchio innanzitutto: da semplice foro, apertura diventa prima di tutto molto più grande, andando a ricoprire i ¾ della superficie totale. La sua trasformazione definitiva è quella in forma cosmica, come si nota con evidenza in “Nexus T2/1”, “Nexus T2/2” e in “Elogio delle apparenze”. In tali opere è possibile osservare, infatti, un geoide costellato di continenti immaginari, sospeso nel vuoto nero e sdoppiato - in “Nexus T2/2” - in quella che potrebbe essere la sua formula matematica corrispondente.

Anche le linee, sempre confrontando con i lavori precedenti, si modificano e vanno ora a suddividere lo spazio in scomparti e in sotto-scomparti, formando pannelli rigati come venature legnose (vedi “Corpoprogetto/1”). Di legno vero e proprio sono, poi, i rametti dipinti e applicati sulla superficie; a rendere l’opera più materica. Possiamo osservarli in “Natura e Psyche” (2 e 3).

Ma è nella parte figurativa di Pezzuco che io rintraccio il più grande sviluppo nelle fasi artistiche del pittore. Se, infatti, fino a questo momento la figura umana o animale è semplicemente sagoma, tratteggio, incisione “rupestre”, ora essa acquista spessore e tridimensionalità, fino a instaurare un rapporto dialettico, come in “Natura e Psyche/1” e “Natura e Psyche/2”.

La tematica dell’“invisibile e tangibile” acquista quindi nuovi significati. Vediamo infatti come i volti raffigurati siano in un rapporto dialogico tra loro, almeno apparentemente. Pezzuco pone infatti questi soggetti anonimi e totalmente decontestualizzati uno di fronte all’altro ma li rappresenta bendati, dando vita a ciò che viene perfettamente espresso nel titolo, ovvero un “Paradosso della visibilità”. Seguendo quell’analisi sociologica della società contemporanea, che ha come fondatore e massimo esponente lo studioso Zygmunt Bauman: i rapporti sociali sono sempre più labili, incerti, soggetti a repentini cambiamenti, a fronte però di una crescente voglia di rendersi “visibili” (che non è ovviamente sinonimo di “veri”) e di un’altrettanto crescente e illusoria pretesa di conoscere e controllare il mondo circostante. Si innesca quindi un paradosso, perfettamente leggibile in questo ciclo di opere, tra la necessità di tutti gli uomini di mettersi in relazione con i propri simili (già Aristotele definiva l’uomo un “animale sociale”), la voglia ossessiva – molto più recente – di essere presenti e notabili in qualche modo e infine l’incapacità sconfortante di osservare l’altro ed essere osservati profondamente e consapevolmente.

I motivi di questo cambiamento di “inquadratura” (usando un termine proprio dell’arte fotografica) possono essere molteplici: potrebbe esserci una volontà – conscia o inconscia – a infondere un maggior senso di equilibrio, di familiarità volendo, nel fruitore e forse nell’autore stesso.

Ipotizzando, si può pensare a una corrispondenza tra le nuove dimensioni fisiche dell’opera e un rinnovato approccio verso i soggetti delle stesse e a quello che io definirei un avvicinamento a un certo tipo di realismo. Soggetti che ora andrò ad analizzare.

La divisione della tavola in più zone, la ricerca sulle forme geometriche di base (come la linea e il cerchio), l’abbozzo di figure umane e naturali e l’inserimento di lettere e simboli matematici sono elementi costanti nella ricerca artistica di Pezzuco, la sua firma. Ciascuno di essi viene però riformulato e riproposto.

Il cerchio innanzitutto: da semplice foro, apertura diventa prima di tutto molto più grande, andando a ricoprire i ¾ della superficie totale. La sua trasformazione definitiva è quella in forma cosmica, come si nota con evidenza in “Nexus T2/1”, “Nexus T2/2” e in “Elogio delle apparenze”. In tali opere è possibile osservare, infatti, un geoide costellato di continenti immaginari, sospeso nel vuoto nero e sdoppiato - in “Nexus T2/2” - in quella che potrebbe essere la sua formula matematica corrispondente.

Anche le linee, sempre confrontando con i lavori precedenti, si modificano e vanno ora a suddividere lo spazio in scomparti e in sotto-scomparti, formando pannelli rigati come venature legnose (vedi “Corpoprogetto/1”). Di legno vero e proprio sono, poi, i rametti dipinti e applicati sulla superficie; a rendere l’opera più materica. Possiamo osservarli in “Natura e Psyche” (2 e 3).

Ma è nella parte figurativa di Pezzuco che io rintraccio il più grande sviluppo nelle fasi artistiche del pittore. Se, infatti, fino a questo momento la figura umana o animale è semplicemente sagoma, tratteggio, incisione “rupestre”, ora essa acquista spessore e tridimensionalità, fino a instaurare un rapporto dialettico, come in “Natura e Psyche/1” e “Natura e Psyche/2”.

La tematica dell’“invisibile e tangibile” acquista quindi nuovi significati. Vediamo infatti come i volti raffigurati siano in un rapporto dialogico tra loro, almeno apparentemente. Pezzuco pone infatti questi soggetti anonimi e totalmente decontestualizzati uno di fronte all’altro ma li rappresenta bendati, dando vita a ciò che viene perfettamente espresso nel titolo, ovvero un “Paradosso della visibilità”. Seguendo quell’analisi sociologica della società contemporanea, che ha come fondatore e massimo esponente lo studioso Zygmunt Bauman: i rapporti sociali sono sempre più labili, incerti, soggetti a repentini cambiamenti, a fronte però di una crescente voglia di rendersi “visibili” (che non è ovviamente sinonimo di “veri”) e di un’altrettanto crescente e illusoria pretesa di conoscere e controllare il mondo circostante. Si innesca quindi un paradosso, perfettamente leggibile in questo ciclo di opere, tra la necessità di tutti gli uomini di mettersi in relazione con i propri simili (già Aristotele definiva l’uomo un “animale sociale”), la voglia ossessiva – molto più recente – di essere presenti e notabili in qualche modo e infine l’incapacità sconfortante di osservare l’altro ed essere osservati profondamente e consapevolmente.

frammenti diversi

cm.50x180

cm.50x180

Terra e vento

Elisabeth Frolet

Eearth and wind... Sensitive description of the art and duplicity of Francesco Pezzuco's painting who seeks with his works to grasp the two extremes of human sensitivity: the material and the immaterial...

In another work, "Chasuble", the material used suggests a more concrete universe: the wood and the ceramic cup, composed in a crescendo of colors, constitute the stages of the knowledge of fullness symbolized by an almost monastic bowl. These three works present themselves in some way as the articulation around which the rest of the exhibition is arranged. The modalities are the same: the circle dominates, symbol of the tonality and of the infinite which marks the rhythm of the succession of small "communicating" paintings: circles, squares, triangles which communicate, which respond to each other through the sharp beat of the sticks, the sound transparent of the enigmatic circles and the muffled note of the dark squares. Francesco Pezzuco manipulates abstraction like a musical melody with light and ethereal resonances. String quartet offering a hymn to lightness. His paintings could be mistaken for small "mandalas", geometric supports for meditation and intermediaries for a spiritual ascension.

Terra e vento... Descrizione sensibile dell’arte e della duplicità della pittura di Francesco Pezzuco che cerca con le sue opere di cogliere i due estremi della sensibilità umana: il materiale e l’immateriale...

In un’altra opera, “Casula”, la materia utilizzata suggerisce un universo più concreto: il legno e la tazza di ceramica, composte in un crescendo di colori, costituiscono le tappe della conoscenza della pienezza simbolizzate da una ciotola pressoché monastica. Queste tre opere si presentano in qualche modo come l’articolazione intorno alla quale si sistema il resto dell’esposizione. Le modalità sono le stesse: il cerchio domina, simbolo della tonalità e dell’infinito che scandisce il ritmo del seguito dei piccoli quadri “comunicanti”: cerchi, quadrati, triangoli che comunicano, che si rispondono attraverso il battito secco delle bacchette, il suono trasparente dei cerchi enigmatici e la nota sorda dei quadrati cupi. Francesco Pezzuco manipola l’astrazione come una melodia musicale dalle risonanze leggere ed eteree. Quartetto di corde che offrono un inno alla leggerezza. I suoi quadri potrebbero essere scambiati per piccoli “mandalas”, supporti geometrici alla meditazione e intermediari di una ascensione spirituale.

frammenti diversi

"la differenza e il probabile "

polimaterico filo a piombo

cm.120x140

"la differenza e il probabile "

polimaterico filo a piombo

cm.120x140

L’isola che non c’è

Bruna Condoleo

The artist's work is therefore not polluted by the present, but is a precious inlay of the mind with which he manages to distance himself from the transitory and the relative...

Investigating the interiority of the soul, aspiring to conquer a metaphysical reality, enhancing the spiritualistic component of the artistic message, means for Pezzuco to re-propose in his pictorial expression a tension towards the universe that shows the artist's will to understand the world . Not a pessimistic vision, nor a devaluation of the society in which we live, despite its vain superficialities: what Pezzuco proposes, through the lyrical and calm language of his works, is a renewed trust in man and in his possibility of finding a dimension of existence more suited to the fundamental needs of the spirit. Then, perhaps, the island… will be there.

L’opera dell’artista non è dunque inquinata dal presente, ma è intarsio prezioso della mente con cui egli riesce ad allontanarsi dal transitorio e dal relativo...

Investigare l’interiorità dell’animo, aspirare alla conquista di una realtà metafisica, esaltando la componente spiritualistica del messaggio artistico, vuol dire per Pezzuco riproporre nella sua espressione pittorica una tensione verso l’universo che mostri la volontà dell’artista di capire il mondo. Non una visione pessimistica, né una svalutazione della società in cui viviamo, malgrado le sue vane superficialità: quella che Pezzuco propone, attraverso il linguaggio lirico e pacato delle sue opere, è una rinnovata fiducia nell’uomo e nella sua possibilità di trovare una dimensione dell’esistere più consona ai fondamentali bisogni dello spirito. Allora, forse, l’isola… ci sarà.

frammenti diversi